The romantic (and possibly Romantic) view of the Internet is that it’s inherently ungovernable and anonymous. But governments of several nations (and smaller political units) around the world have for years imposed various kinds of restrictions, including age-related ones, on the users of specific software, sites, or even the entire Internet. That practice, when framed in terms of protecting children, can take the form of age gating — for example, asking visitors to a site whether they’re at least 18 years old.

That approach is back in the news because of the United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act, which was passed in 2023 and took effect on July 25, 2025. It requires online “platforms” — which it defines extraordinarily broadly to include “any site accessible in the UK” — to use “highly effective age assurance to prevent children from accessing pornography, or content which encourages self-harm, suicide or eating disorder content”. It requires that such platforms “also prevent children from accessing other harmful and age-inappropriate content such as bullying, hateful content and content which encourages dangerous stunts or ingesting dangerous substances.”

The United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act…requires online “platforms” to use “highly effective age assurance to prevent children from accessing pornography, or content which encourages self-harm, suicide or eating disorder content” and

“prevent children from accessing other harmful and age-inappropriate content such as bullying, hateful content and content which encourages dangerous stunts or ingesting dangerous substances.”

Similar laws are also being proposed, or already on the books, in several states in the USA. At the federal level, the Kids Online Safety Act (“KOSA”) – currently before Congress – contains similar provisions.

These measures are meant to address an obvious flaw with age-gating methods: they rely on something like a honor system! They have no independent way to check that a user’s answer to the question, “How old are you?” is accurate. (Confession: I routinely put in made-up birth dates when asked for my age, when I see no good reason for them to know anything more than that I’m old enough to be able to visit their site or use their app.) The step beyond age gating is age verification: seeking evidence beyond the would-be user’s attestation, “I swear that I am not making this up”, of their age.

Some child advocacy groups have been instrumental in pushing for the passage of the Online Safety Act and its age verification cousins. That makes sense: adults have both ethical and legal responsibilities to protect children from avoidable and serious harms. If it’s harmful to children for them to see pornography or other material, then there is a prima facie (“on its face”, “on the surface”, “at first glance”) case for keeping kids away from that material. And these laws are saying what many people have screamed for decades now: that powerful platforms have duties of care to their most vulnerable users, not just duties of profitability to their shareholders.

For the moment, let’s also assume that the government – not as an abstraction, but as the specific collection of people who are in office or in agencies that would be enforcing the regulation – is the best-suited entity for determining whether, and how, pornography etc. is harmful. In other words, the judgement of other entities, such as parents, online platform operators, or even kids themselves, is mostly irrelevant.

But (as you knew was coming) those laws have consequences that many people — including child advocacy groups — might not like. The normalizing of age verification systems is not a small thing. If it’s being done in the name of protecting children from harmful material, then how will we know whether it’s working? More to the point: how will we know whether it’s working better than some alternative course of action (including, as one alternative, the status quo)? Are there more fine-grained approaches that could help to protect users of all ages from encountering harmful (or “harmful”) material on online platforms?

We can’t just count the rings in their trunks

An age verification requirement for kids is actually an age verification requirement for every single “platform” user, including adults, to prove their age. What method or evidence reliably establishes a kid’s (or anyone else’s) age?

Vincent Adultman, a character from the TV series Bojack Horseman who is secretly 3 kids in a trench coat

Almost certainly, the answer involves some kind of biometric identification, legal documentation, other officially recognized evidence, or fancy guessing involving behavioral analysis. The task of verifying that information is the platforms’ responsibility, but they have some discretion over how they meet that responsibility. Larger, wealthier ones (think of Meta or YouTube) might take on that responsibility themselves. Other platforms (think of Wikipedia or of an independent app developer) will probably have to subcontract that task to third-party age verification companies. In either case, recall that we’re talking about millions and millions of users. That’s a lot of sensitive information that millions and millions of people would be required to provide to someone. Who vets those companies’ data collection, transmission, storage, and security practices? Who will be liable when, inevitably, that information is intentionally or unintentionally compromised?

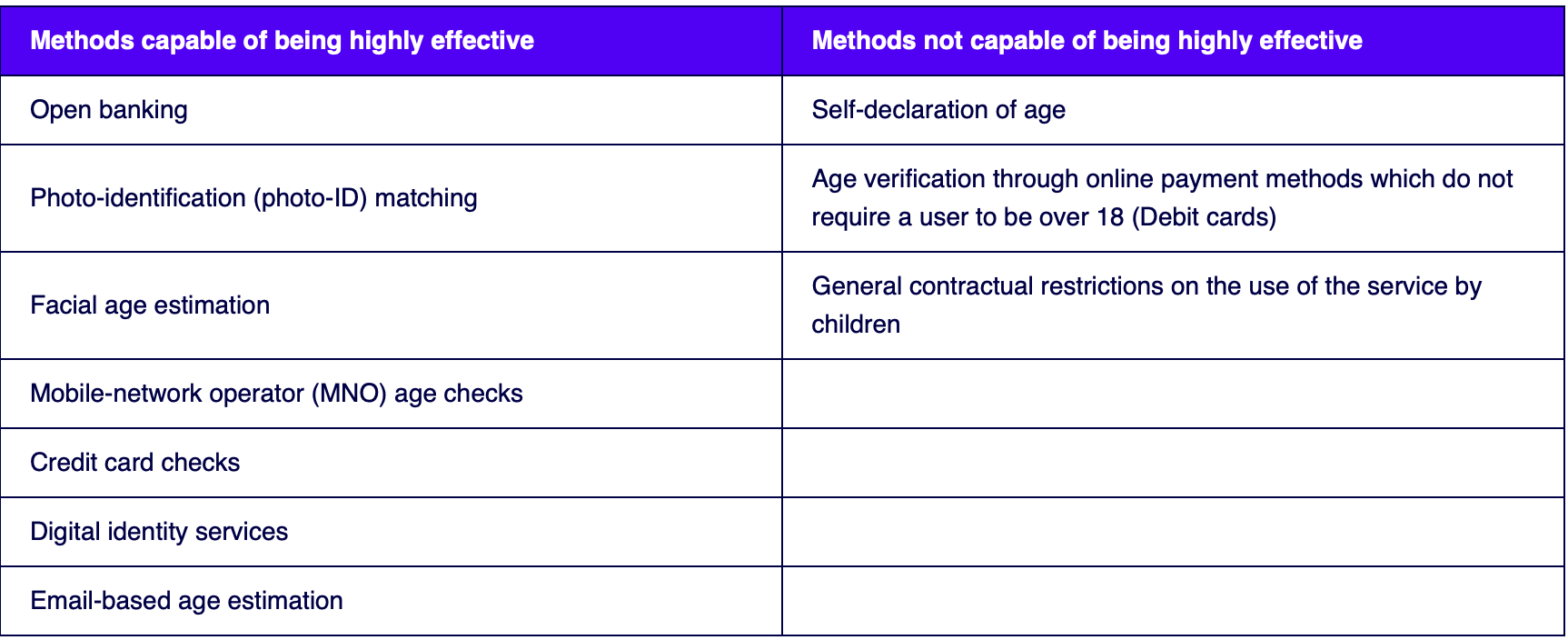

A chart from Ofcom’s “Quick guide to implementing highly effective age assurance”, showing age verification “capable of being highly effective” in one column and other methods “not capable of being highly effective” in another column.

We will all be “protected” from lifesaving information

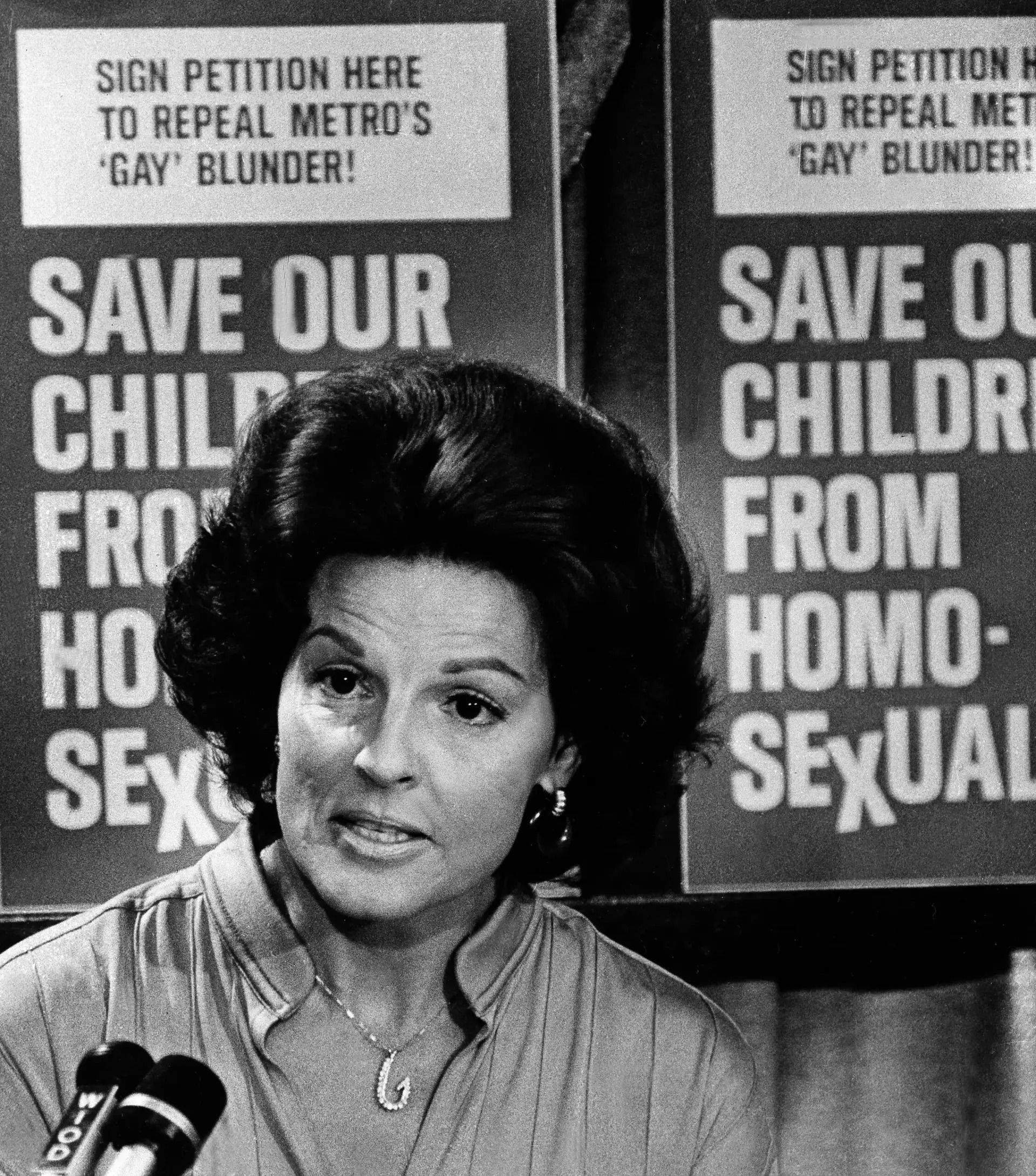

Some of the politicians and activists who have been instrumental in drafting and passing online age restrictions in recent years, define “pornography” very differently than the standard definition of “sexually explicit or graphic materials”. Instead, they use the term to assert that any mention or depiction of LGBTQ people, not just graphic presentation of LGBTQ (and other) relationships or acts, is harmful to kids. It would be irresponsible to leave that context out of the discussion. It would also be historically inaccurate, because we’ve seen this commercial before.

Anita Bryant’s notorious 1970s Save Our Children campaign

Will some online platforms decide that the simplest thing to do is to prohibit all material about or mentioning LGBTQ people for all users, regardless of their age? Such a move would make it more difficult for anyone, adult or child, to discuss their own lives and to access reliable and trustworthy information about the existence and experiences of people of all gender and sexual identities. Such information can be crucial for preventing mental and physical harm, including self-harm.

Security Theater, part MMDXIII

We all know that there’s a significant difference between saying, “Your plan is terrible” and saying, “The concern that your plan is designed to address isn’t real”. However, as the seriousness of the concern increases, so does the difficulty of keeping that difference in mind. So, let’s be clear: people of all ages can be harmed — albeit in different ways and to different degrees — in online spaces, just as they can in offline ones. As kids are especially vulnerable to such harms, we all have legitimate concerns for kids’ online safety. It’s reasonable to want to enlist the providers of those online spaces themselves in protecting kids. And there are many thoughtful criticisms of the role that ubiquitous sexually explicit materials have played in shaping the sexual attitudes, expectations, experiences of generations of people.

That previous paragraph, by the way, is called the “To be sure…” section. People who write essays like this one for a public audience, are taught to always include a To be sure section, where they make a halfhearted nod to the possibility that maybe the view they’re criticizing isn’t entirely bad or based on flimsy reasoning. And the thing that comes immediately after the To be sure section is the explanation of why, even if the view isn’t entirely bad or based on flimsy reasoning, it’s still really bad or flimsy. So, here we go:

But “we must protect the children” plays the same role, both rhetorically and in terms of policy discussions, that “we must prevent terrorism” plays. It’s a thought-terminating cliché. When it comes packaged with a specific set of proposals about how to protect the children (or prevent terrorism), it puts anyone with qualms on the back foot: their qualms about solutions are readily misinterpreted as qualms about the reality of the problems themselves. Furthermore, in both cases, the burden of proof mysteriously seems to vanish from the shoulders of the person who’s seeking greatly to reduce other people’s abilities to move through the world. But in this case, let’s try to keep that burden where it belongs.

Will users in jurisdictions with age restrictions turn, en masse, to virtual private networks (VPNs) and other location-spoofing tools to appear that they’re in an out-of-jurisdiction location? (Signs point to “Yes”.) To prevent that possibility, which governments will simply try to ban the use of VPNs altogether? Which online platforms will simply institute a blanket age verification policy for all users, regardless of their location? In other words - as we already see happening — will companies everywhere just decide that the easiest thing to do is to check everyones’ ages?

Consider what it might mean to have to provide sensitive information merely in order to be able to use online platforms. For example, suppose it were no longer possible for people to participate in online support groups without first supplying such information. How will people’s online behaviors change if anonymous or pseudonymous uses become much harder or even impossible?